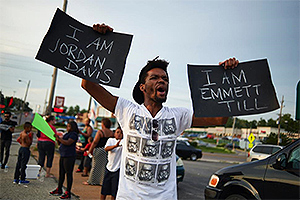

The names and dates and places change, but there is a sad sameness about each episode: there is a confrontation between a young black man and a white police officer, shots are fired, the young black man dies, and the facts are obscured by uncertain investigations and conflicting eyewitness accounts. Outraged protests follow, the peace of the community is shattered, everybody promises to "do something," and the incident is soon forgotten except by those suffering the most painful and intimate loss.

This time the names were Michael Brown and Darren Wilson, and the dates were several days following August 9, and the place was the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Missouri. Brown, age 18, and a friend were walking in the street at noon that Saturday when a police officer in a squad car told them to walk on the sidewalk. A confrontation occurred, Brown was shot several times, and his dead body left in the street for several hours. Though he would later be linked to stealing cigars from a convenience store just a few minutes before the shooting, the officer didn't know that. Protests and demonstrations turned violent, threats were made against the police, and it was six days before they felt it safe to identify the officer as Darren Wilson.

This time the names were Michael Brown and Darren Wilson, and the dates were several days following August 9, and the place was the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Missouri. Brown, age 18, and a friend were walking in the street at noon that Saturday when a police officer in a squad car told them to walk on the sidewalk. A confrontation occurred, Brown was shot several times, and his dead body left in the street for several hours. Though he would later be linked to stealing cigars from a convenience store just a few minutes before the shooting, the officer didn't know that. Protests and demonstrations turned violent, threats were made against the police, and it was six days before they felt it safe to identify the officer as Darren Wilson.

Although retired basketball superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, now 67, writing for Time Magazine, described the Ferguson conflict as "class warfare" rather than "systematic racism," he also identified a divide we seem unable to bridge:

[T]o many in America, being a person of color is synonymous with being poor, and being poor is synonymous with being a criminal.

Skin is like wrapping paper; a package wrapped in brown paper is not made different or better when wrapped in white. That obvious truth is diminished by presuppositions we can't quite shake. As a boy riding my red bicycle, I was never once stopped by the police and asked, "Hey, Boy, where are you going with that bicycle? Where'd you get it, anyhow?" My black-skinned grandson has had that experience and heard those exact words at least twice.

Every Ferguson needs a level-headed, compassionate leader to calm the community outrage while understanding the emotion that produces it. In Missouri that leader was a 51-year-old, 27-year veteran of the Missouri Highway Patrol, married, and the father of two adult children. Captain Ron Johnson commands Troop C, covering 11 counties with 147 uniformed officers and 157 civilian employees. His superior officer, Major Bret Johnson (not related), said:

He happened to be here, and he happened to be African-American. He was perfect for [the job]. God took care of us there in that respect.

When Governor Jay Nixon put Captain Johnson in charge five days after the shooting, Johnson described how he went in the men's room:

[I] closed the door and looked in the mirror, and just began to pray. I just asked God to let me do the right thing. Do the thing that would be right for everybody.

When Captain Johnson hit the streets of Ferguson, where he had grown up and still lives nearby, the large man with all his police paraphernalia, and muscles straining his uniform seams could easily have met force with force. But he chose handshakes and hugs instead, renewing acquaintances, and assuring residents that he was there as a friend:

When this is over, I'm going to go in my son's room, my black son - who wears his pants saggy, his hat cocked to the side, he's got tattoos on his arms....

I wish I could know Ron Johnson, a man who could weep with an angry mob and win them over with a few sentences:

I wish I could know Ron Johnson, a man who could weep with an angry mob and win them over with a few sentences:

This is my neighborhood. You are my family. You are my friends. And I am you.

I am privileged to know another Man who said something very much like that:

Greater love has no one than this, that he lay down his life for his friends. You are my friends...

Jesus said it as some of his last words to his closest disciples right before his betrayal, trials, and crucifixion (John 15:13-14). Later, the great encourager who gave us the New Testament book of Hebrews described our friend Jesus as one who is able:

...to empathize with our weaknesses... one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are - yet he did not sin. Let us then approach God's throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help us in our time of need (Hebrews 4:15-16).

Jesus' life says to us something very similar to what Ron Johnson said to a group of hurting and angry people: "This is my neighborhood. You are my family. You are my friends. And I am you."

And because of this, we can turn to Jesus with confidence in our times of need!

Comments

Have thoughts on this article? Leave a comment