Special Note:

I love Jordan Harrell's writing because she challenges me to re-examine what I think I know. I have known her for much of her life, going back to when she was a little girl. Her parents went on a few vacations with us. Her dad, Jim, the writer of most of this post, grew up next door. We lived a bit out in the country. In a time of division and racial strife, we need those who are honest about our journeys to this current day in which we find ourselves. This post is special. Please read it carefully. Think about it. Ask the Holy Spirit to lead us all to more a Kingdom glorifying reality that, thankfully, many of our children and grandchildren pursue.

Yesterday was my dad's birthday.

He's never exactly fit a mold. He's a former college quarterback and coach and a former children's minister with a Master's in Religious Education. He loves calculus and church history, classical music, and baseball. He writes essays for fun.

His relationship with religion has always felt complicated, something he's been transparent about since I was an adult through dozens of conversations that have made me feel okay in my doubt.

His cynicism and questioning were gifted to me at birth and have affirmed and challenged me ever since.

His parents, Leon and Iris, were devout members of the Church of Christ. During the Depression in the 1930s, when Abilene Christian University (ACC at the time) was about to go bankrupt, Leon's dad, JC, went to a rancher near Lubbock and secured a large loan that saved the university. JC called home and told my grandpa, a child at the time, to go ring the bell on campus to let everyone know the school was saved.

I tell this story to preface the next story.

Our religious roots run very deep and very wide, which is a blessing in many ways but can make other things a bit hard to untangle.

My dad has been untangling for a while, so in honor of his 67th birthday, I want to share part of one of his "essays for fun." As I decolonize and deconstruct, I find going backward is necessary before we truly can go forward. He wrote this five years ago. I hope you'll take a second to read it.

In 1966, I was a 12-year-old and a sports-minded kid playing basketball. I played for Taylor, the white segregated elementary school in our part of town. We were playing Woodson, the all-black segregated elementary school.

In the small gym, all fans sat in folding chairs a few feet from the court's sidelines. My parents and my dad's parents were sitting in that section.

As the game progressed, the ball went out of bounds. Two players dove to retrieve it (one player from Taylor and one from Woodson). The black player from Woodson accidentally dove into my grandparents' chairs, in particular hitting my granddad, nearly knocking him on the floor. A gentle and quiet man, this is the only time I can remember Granddaddy losing his temper.

I froze as I stood on the court and watched Granddaddy scream at the boy, unleashing a racist and profanity-laden verbal assault on the innocent and unsuspecting black child.

My dad intervened and "dressed down" my granddad very directly and restored a measure of calm to the situation.

I was simultaneously stunned at what my granddad had done and proud of my father for his "righteous indignation" directed toward his own father.

In that gym, I began a slow, intellectual journey that I continue today, wondering why 'it's just the way things are' is an excuse for behavior and systems that are against the spirit of Christ.

I've been a teacher and a coach most of my adult life, and for the last five years, I've been teaching at a small alternative campus for high school students who are behind academically.

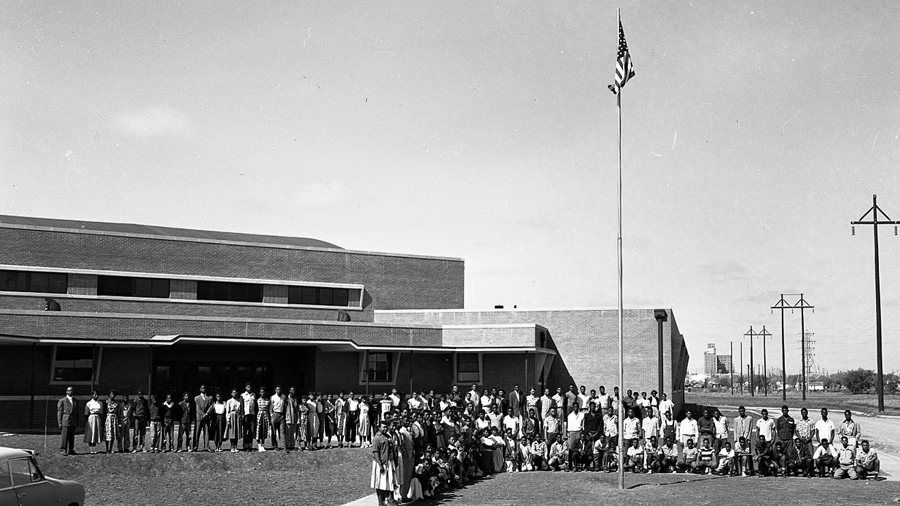

The building for this school is where segregated black junior high and high school students went to school in the 1950s and '60s.

Every day when I walk to the office, I pass by a display case with pictures.

It took me multiple journeys past this display before I actually noticed what was in the case-two pictures of the 1954 Woodson High School varsity boys' basketball team.

It was the fall of 1954, the first full year of operation for the "new" Woodson Jr. High and Sr. High campus. All 12 grades of the segregated black school were located at this campus. It was in the heart of the poorest section of town. It was known as the Abilene Colored School.

1954 was the year that "Brown vs. Board of Education" declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

1954 was the year I was born.

I knew most of the names of the faces of the players from the '54 team. Some were parents of friends I played little league with, one a famous restaurant owner that had died just a few years earlier, one a Texas high school Hall of Fame football coach.

As I studied the faces on that picture, I began the uncomfortable process of real education - what "separate but equal" meant to the lives, to the spirit, of every black child at the school where I now teach.

Woodson was never given "new" - only the hand-me-down, old and tattered equipment and textbooks from the all-white high school.

Dorothy Wiseman, a retired teacher who went to Woodson as a student and also taught there, recalls, "We always had out-of-date, used textbooks. When I was issued a textbook, the student name section on the inside front cover was already filled out." Wiseman reflects, "something as simple as not having a place to write her name in her textbook left an unforgettable mark on me as an individual."

"Unforgettable mark" - the context is a tragic one. So, I've been asking myself lately...

What happens when an entire generation of children grows up believing they are invisible, that they don't matter?

Why are there a disproportionate number of black and Hispanic children at my school, which is primarily for children who have fallen behind?

How could Granddaddy have been so blind? He was an otherwise good man. How did entire generations of intelligent and "Christian" people miss it so badly?

And an even harder and more frustrating question might be, "what are our blind spots today?" Is there a way to remove the "boulders" in our own eyes as we attempt to see as Jesus did?

This question draws me toward the gospel of John and the story of the man born blind. As he talks about this "sign" of Jesus, John, from the beginning of the story, uses the miracle of physical healing of blindness to move toward the more urgent understanding of spiritual blindness.

At the end of John chapter 9, after the blind-man-now-healed realizes he is talking to the Son of Man the Messiah, he simply responds to Jesus by saying, "Lord!" Then Jesus says, "I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind."

The Pharisees heard him say this and said, "Surely we are not blind, are we?" Jesus then tells them, "If you were blind, you would not have sinned. But now that you say, 'We see', your sin remains."

The weight of this story shouldn't sit well with church leaders whose tendency is to imitate (possibly unconsciously) the very same religious leaders of Jesus' day.

The great paradox never changes with time. The only truly Christian virtue is humility.

For any church to see rightly may have nothing to do with the proper vision statement or the latest leadership training from the coolest business pied piper. Everything to do with a call to return to the heart of the gospel story begins with humility and the fear of the Lord. The Kingdom is where Jesus calls all true believers to have eyes that "see" the poor as inheriting the kingdom of heaven, the homeless as having the same chances to receive opportunities to change, and kingdom leadership in the church that begins with humility.

Are we resigned to always look back in time and say, "we were really blind about..."? I don't honestly know.

But isn't it possible that in whatever context we find ourselves now, whatever systemic sin we battle against in our lives and our communities, we can live through an authentic restoration vision that believes God is making all things new?

And, to agree that the best church vision will have less to do with programs, budgets, and plans, and more to do with God's desire to give us all eyes to see as our Lord, and the wisdom and courage to act.

I repeat: he wrote this five years ago.

I leave you with this - what's our blind spot today?

If history tells us anything, we've got one.

Comments

Have thoughts on this article? Leave a comment