|

|

|

December 16 When

I called Vera today she apologized for how she had rushed out of the art shop

without saying “Ahoj.” (For some reason, the land-locked Czechs have a fancy

for the sea, so their informal way of saying hello and good-bye is the sailor’s

expression, Ahoj.) “It was too painful for me,” she slowly but sadly

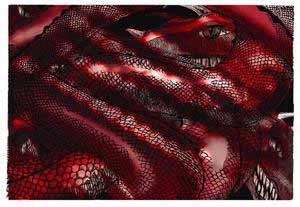

mumbled. I asked Vera to join us for dinner tonight, thinking that being with our children might be good for her and give me a chance to process what we both had seen and felt while looking at the 2nd picture. After dinner and a pleasant conversation about our kids and Christmas customs, Vera asked if we had ever heard the story of Jan Palach. I knew that there was a statue of him on Saint Wencelas square, that he died as a young man in 1968, but that was about all I knew. She then, in her clear and methodical story-telling style, recounted what had happened in her homeland in 1968. “It was the Prague Spring,” she wistfully stated. As she went on to recount, during the spring of 1968 hopes of freedom reached an all-time high in what was known then as Czechoslovakia. The Russians still occupied Prague, as they did the other Warsaw Pact satellites like Poland and Hungary, though there seemed to be a thaw of the icy relations between Prague and Moscow. The talk on the Prague streets and in beer halls and coffee houses was of one thing: freedom. The thaw was, tragically, short-lived. Moscow decided that the Czechs were thinking and acting with a bit too much liberty and not enough respect for communism. So, on August 21, 1968, Russian tanks rolled through the streets of Prague, destroying anything and anyone who dared to get in the way. Some lost their lives. Even more, a country — and all of East Europe for that matter — lost their hope. One of those was a young university student, Jan Palach. He was so overwhelmed with hopelessness and despair, he ignited himself as a demonstration to the Soviets that life under communism is not a life worth living. Moscow barely noticed. The Czechs, however, were touched and angered to the core. They built a statue to remember his life. Vera went on to tell me that when she saw the wood carving of Red Dragon, ready to destroy the child, she thought of Palach’s life and death. She thought of her homeland and of her own life; how it seemed all too real that someone or something was out for blood. I had no words of comfort or wisdom to pass along. We all just sat in silence for a few minutes when I somehow remembered the Lord’s prayer and especially the last line: “deliver us from evil.” We ended our evening by praying the Lord’s prayer together. I believe this is the first time we have prayed together. I hope it won’t be the last. |

|